Chapter 30 - Makefiles

Writing programs can be a fun thing to do. By expressing ourselves in a high-level language we can actually tell a computer or embedded system, which only understands low-level binary, what to do. This high-level language needs to be translated to binary processor instructions specific for the architecture the application will be running on. This is a job for compilers and interpreters.

Compiling source code (the high-level language) can be a very complex job, especially when your project starts to become big and complex. Modern IDE (Integrated Development Environments) such as Visual Studio and Eclipse have spoiled us a bit on this matter. However in the Linux and embedded world you do not always have these tools at your disposal. This is where makefiles can make our life's a little easier. Makefiles are textual files that tell a compiler how the source code has to be build into an executable program. This approach is also preferred as it allows for automated build processes and such.

While makefiles can be as complex as the projects they build, they are often generated or build step by step. In this chapter a brief introduction in makefiles is given.

The C++ Compilation Process

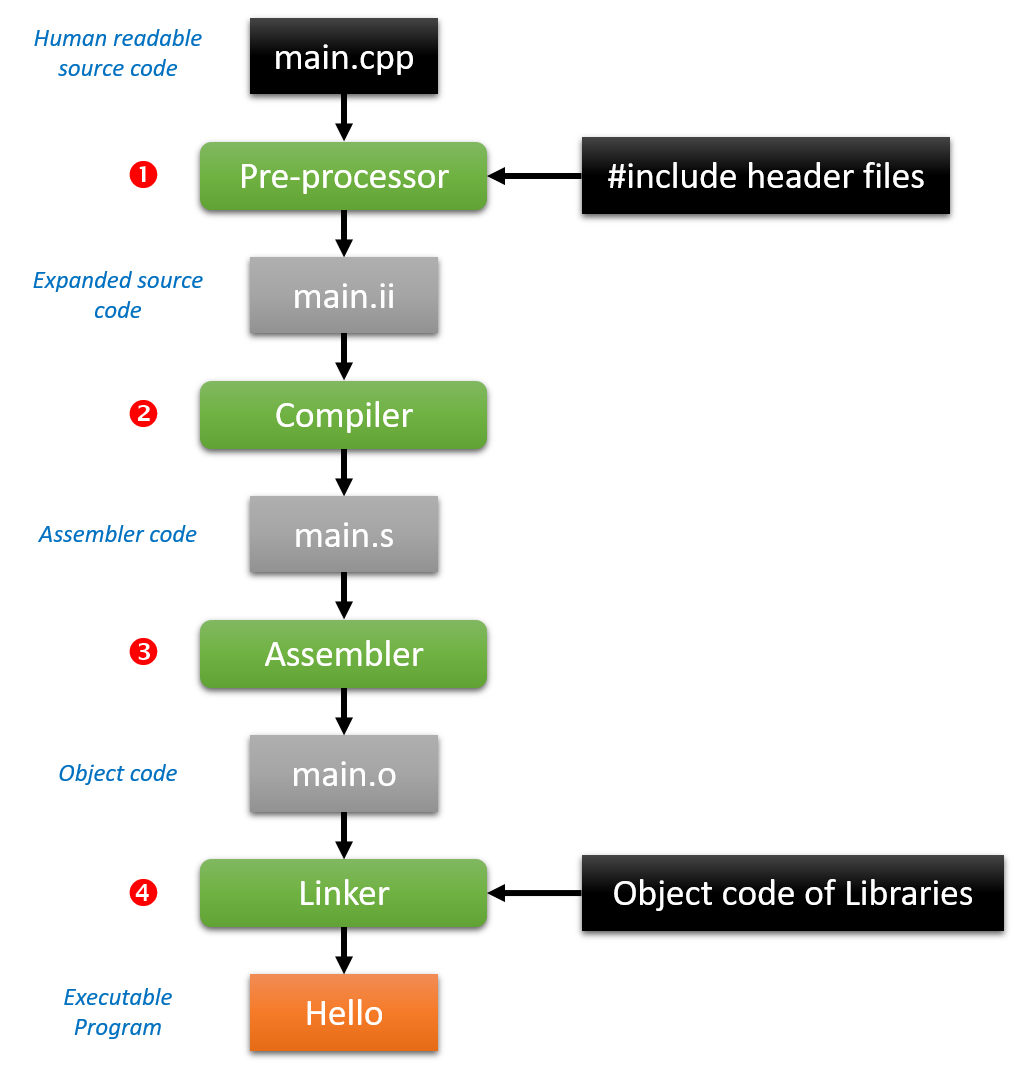

Compiling a C++ source code file into an executable program is a four-step process. To compile for example a single main.cpp file containing a basic hello world application, one could use the g++ command to compile it into an executable binary:

g++ -Wall -o Hello main.cpp -save-temps

-Wall tells the compiler to show all warnings as they may describe possible errors in your source code. If warnings are the only messages you get when you compile your source code, an executable will still be created. However it is good practice to fix the code to get no warnings or errors at all.

-save-temps tells the compiler to save all intermediate files to the compilation folder (pre-processed files, object files, ...).

In the example above the compilation process looks like this:

The C++ preprocessor copies the contents of the included header files into the source code file, generates macro code, and replaces symbolic constants defined using

#definewith their values. The output of this step is a "pure" C++ file without any pre-processor directives (which start with a#). It also adds special markers that tell the compiler where each line came from so that these can be used to produce sensible error messages. The "pure" source code files can be really huge. Even a simple hello world program is transformed into a file with about 11'000 lines of code.The expanded source code file produced by the C++ pre-processor is fed to a compiler and compiled into the assembly language for the platform.

The assembler code generated by the compiler is assembled into the object code for the platform. Object files can refer to symbols that are not defined. This is the case when you use a declaration, and don't provide a definition for it. The compiler doesn't mind this, and will happily produce the object file as long as the source code is well-formed. Compilers usually let you stop compilation at this point. This is very useful because with it you can compile each source code file separately. The advantage this provides is that you don't need to recompile everything if you only change a single file. This will later integrate perfectly with makefiles.

The object code file generated by the assembler is linked together with the object code files for any library functions used to produce an executable file. It links all the object files by replacing the references to undefined symbols with the correct addresses. Each of these symbols can be defined in other object files or in libraries. If they are defined in libraries other than the standard library, you need to tell the linker about them. The output of the linker can be either a dynamic library or an executable.

Difference between GCC and G++

Both gcc and g++ are compiler-drivers of the 'GNU Compiler Collection' (which was once upon a time just the 'GNU C Compiler', but it eventually changed when more languages were added.).

HINT - GNU

GNU is an operating system and an extensive collection of computer software. GNU is composed wholly of free software, most of which is licensed under GNU's own GPL (General Purpose License). GNU is a recursive acronym for "GNU's Not Unix!", chosen because GNU's design is Unix-like, but differs from Unix by being free software and containing no Unix code. The GNU project includes an operating system kernel, GNU HURD, which was the original focus of the Free Software Foundation (FSF). However, non-GNU kernels, most famously Linux, can also be used with GNU software; and since the kernel is the least mature part of GNU, this is how it is usually used. The combination of GNU software and the Linux kernel is commonly known as Linux (or less frequently GNU/Linux).

The programs gcc and g++ are not compilers, but really drivers that call other programs depending on what arguments you provide to them. These other programs include macro pre-processors (such as cpp), compilers (such as cc1), linkers (such as ld) and assemblers (such as as), as well as others, most of which are part of the GNU Compiler Collection (some are assumed to be on your system).

The actual compiler is cc1 for C and cc1plus for C++.

Even though they automatically determine which compiler to call depending on the file-type, unless overridden with -x language flag, there are some important differences.

The main differences between gcc and g++ are:

- gcc will compile: .c/.cpp files as C and C++ respectively.

- g++ will compile: .c/.cpp files but they will all be treated as C++ files.

- Also if you use g++ to link the object files it automatically links in the std C++ libraries (gcc does not do this).

- gcc compiling C files has less predefined macros.

- gcc compiling .cpp and g++ compiling .c/.cpp files has a few extra macros.

So basically, the most important difference is which libraries they link against by default.

g++ is equivalent to gcc -xc++ -lstdc++ -shared-libgcc (the -xc++ is a compiler option, while -lstdc++ and -shared-libgcc are linker options).

Compiling Hello World

A simple hello world example:

// main.cpp

#include <iostream>

int main(void) {

std::cout << "Hello world from C++" << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Compiling this with g++ results a fine working program:

g++ main.cpp -o hello

Running the hello binary results in

Hello world from C++

Trying to do the same with gcc results in linking errors:

gcc main.cpp -o hello

/tmp/ccg5ztrG.o:main.cpp:(.text+0x21): undefined reference to `std::cout'

/tmp/ccg5ztrG.o:main.cpp:(.text+0x26): undefined reference to `std::basic_ostream<char, std::char_traits<char> >& std::operator<< <std::char_traits<char> >(std::basic_ostream<char, std::char_traits<char> >&, char const*)'

/tmp/ccg5ztrG.o:main.cpp:(.text+0x2d): undefined reference to `std::basic_ostream<char, std::char_traits<char> >& std::endl<char, std::char_traits<char> >(std::basic_ostream<char, std::char_traits<char> >&)'

/tmp/ccg5ztrG.o:main.cpp:(.text+0x34): undefined reference to `std::ostream::operator<<(std::ostream& (*)(std::ostream&))'

/tmp/ccg5ztrG.o:main.cpp:(.text+0x54): undefined reference to `std::ios_base::Init::~Init()'

/tmp/ccg5ztrG.o:main.cpp:(.text+0x75): undefined reference to `std::ios_base::Init::Init()'

collect2.exe: error: ld returned 1 exit status

However if we repeat the command but inform the linker to link in the standard C++ libraries all is well:

gcc main.cpp -lstdc++ -o hello

Conclusion: don't make your life more complex than needed and use g++ to compile your C++ and C programs.

Makefiles

Compiling your source code files can be tedious, specially when you want to include several source files and have to type the compiling command everytime you want to do it. Well, I have news for you ... Your days of command line compiling are (mostly) over, because you will learn how to write basic Makefiles.

Makefiles are human readable special format files that together with the make utility will help you to automagically build and manage your projects.

The makefile directs the make tool on how to compile and link a program. Some common action that need to be taken when using C/C++ as an example:

- When a C/C++ source file is changed, it must be recompiled.

- If a header file has changed, each C/C++ source file that includes the header file must be recompiled to be safe.

- Each compilation produces an object file corresponding to the source file. Finally, if any source file has been recompiled, all the object files, whether newly made or saved from previous compilations, must be linked together to produce the new executable program.

These instructions with their dependencies are specified in a makefile. If none of the files that are prerequisites have been changed since the last time the program was compiled, no actions take place. For large software projects, using Makefiles can substantially reduce build times if only a few source files have changed.

Separate Compilation

One of the features of C and C++ that's considered a strength is the idea of "separate compilation". Instead of writing all the code in one file, and compiling that one file, C/C++ allows you to write many .cpp files and compile them separately. With few exceptions, most .cpp files have a corresponding .h file.

A .cpp usually consists of:

- the implementations of all methods in a class,

- standalone functions (functions that aren't part of any class),

- and global variables (usually avoided).

The corresponding .h file contains:

- class declarations,

- function prototypes,

- and extern variables (again, for global variables).

- The purpose of the .h files is to export "services" to other .cpp files.

For example, suppose you wrote a Vector class. You would have an .h file which included the class declaration. Suppose you needed a Vector in an ArrayList class. Then, you would write #include "vector.h".

Why all the talk about how .cpp files get compiled in C++? Because of the way C++ compiles files, makefiles can take advantage of the fact that when you have many .cpp files, it's not necessary to recompile all the files when you make changes. You only need to recompile a small subset of the files. Back in the old days, a makefile was even more convenient as compiling was very slow. Therefore, having to avoid recompiling every single file meant saving a lot of time.

Although it's much faster to compile these days, it's still not very fast. If you begin to work on projects with hundreds of files, where recompiling the entire code can take many hours, you will still want a makefile to avoid having to recompile everything.

Basics of Makefiles

A makefile is based on a very simple concept. A makefile typically consists of many entries. Each entry has:

- a target (usually a file)

- the dependencies (files which the target depends on)

- and commands to run, based on the target and dependencies.

Let's look at a simple example.

student.o: student.cpp

g++ -Wall -c student.cpp

-Wall has already been explained but -c has not. It tells the compiler to compile the code into an object file and stop there. This allows us to compile all .cpp files into object files and later link them all together into a single executable file.

WARNING - TABS

Please note that make depends heavily on indentation (a bit like python). This means that the commands of a target need to be prefixed with a single tab character, no more, no less. The tabs should also be tab characters and no spaces.

The basic syntax of an entry looks like:

<target>: [ <dependency > ]*

[ <TAB> <command> <endl> ]+

As with other programming, we also like to make our makefiles as DRY (Don't Repeat Yourself) as possible. For this reason the compiler, the compiler flags and linker flags are often set as variables in the makefile, allowing them to be reused and changed quickly if needed.

Let's see an example for a simple hello world program with a single main.cpp file:

# The compiler to use

CC=g++

# Compiler flags

CFLAGS=-c -Wall

# -c: Compile or assemble the source files, but do not link. The linking stage simply is not done. The ultimate output is in the form of an object file for each source file.

# -Wall: This enables all the warnings about constructions that some users consider questionable, and that are easy to avoid (or modify to prevent the warning), even in conjunction with macros.

# Name of executable output

EXECUTABLE=hello

$(EXECUTABLE): main.o

$(CC) main.o -o $(EXECUTABLE)

main.o: main.cpp

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) main.cpp

Notice how the compilation of the main.cpp file and the eventual linking of all object files (is this case only one, excluding libraries) is split into two targets.

Now to start the make process all you need to do is traverse to the directory with the Makefile in it and execute the make command with a target specified:

make hello

g++ -c -Wall main.cpp

g++ main.o -o hello

This should result in the following files:

hello main.cpp main.o Makefile

HINT - Make for Windows

Make is automatically installed on Linux when you installed the

build-essentialpackage. For Windows, make can be downloaded at http://gnuwin32.sourceforge.net/packages/make.htm. Make sure to add make to the PATH of your user, typicallyC:\Program Files (x86)\GnuWin32\bin.

Most makefiles will also include an 'all' target. This allows the compilation of the full project. The 'all' target is usually the first in the makefile, since if you just write make in command line, without specifying the target, it will build the first target. And you expect it to be 'all'.

Another frequent target is the 'clean' target. This removes both the executable and all intermediary files that were generated.

With both these targets added, the makefile becomes:

# The compiler to use

CC=g++

# Compiler flags

CFLAGS=-c -Wall

# -c: Compile or assemble the source files, but do not link. The linking stage simply is not done. The ultimate output is in the form of an object file for each source file.

# -Wall: This enables all the warnings about constructions that some users consider questionable, and that are easy to avoid (or modify to prevent the warning), even in conjunction with macros.

# Name of executable output

EXECUTABLE=hello

all: $(EXECUTABLE)

$(EXECUTABLE): main.o

$(CC) main.o -o $(EXECUTABLE)

main.o: main.cpp

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) main.cpp

clean:

rm -f *.o $(EXECUTABLE)

A More Complex Hello World Example

Now what if your project contained more files than just a simple main.cpp file. This will be the case for most projects.

The makefile below shows how separate classes can be compiled using a makefile.

# The compiler to use

CC=g++

# Compiler flags

CFLAGS=-c -Wall

# -c: Compile or assemble the source files, but do not link. The linking stage simply is not done. The ultimate output is in the form of an object file for each source file.

# -Wall: This enables all the warnings about constructions that some users consider questionable, and that are easy to avoid (or modify to prevent the warning), even in conjunction with macros.

# Name of executable output

EXECUTABLE=hello

all: $(EXECUTABLE)

# The executable depends on all the separate object files

$(EXECUTABLE): main.o robot.o

$(CC) main.o robot.o -o $(EXECUTABLE)

main.o: main.cpp

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) main.cpp

robot.o: lib/robot.cpp

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) lib/robot.cpp

clean:

rm -f *.o $(EXECUTABLE)

A Generic Makefile

A more generic but a bit less readable makefile is shown next. It automatically compiles all .cpp files in a subdirectory src and places the final executable in a directory bin. The only downside is that it only works on Linux.

# The compiler to use

CC=g++

# Compiler flags

CFLAGS=-c -Wall -std=c++11

# -c: Compile or assemble the source files, but do not link. The linking stage simply is not done. The ultimate output is in the form of an object file for each source file.

# -Wall: This enables all the warnings about constructions that some users consider questionable, and that are easy to avoid (or modify to prevent the warning), even in conjunction with macros.

# Linker flags

# LDFLAGS=

# Libraries

# LIBS=

# Name of executable output

TARGET=hello

SRCDIR=src

BUILDDIR=bin

OBJS := $(patsubst %.cpp,%.o,$(shell find $(SRCDIR) -name '*.cpp'))

all: makebuildir $(TARGET)

$(TARGET) : $(OBJS)

$(CC) $(LDFLAGS) -o $(BUILDDIR)/$@ $(OBJS) $(LIBS)

%.o : %.cpp

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) $< -o $@

clean :

rm -rf $(BUILDDIR)

rm -f $(OBJS)

makebuildir:

mkdir -p $(BUILDDIR)