Chapter 02 - Introduction to C++

This chapter will introduce the basics of the C++ language. It does expect you to already be familiar with another programming language such as Java.

Variables

While programming in any programming language, you need to reserve memory when you wish to store data. This can be achieved by using variables. When you create a variable, you actually reserve space in memory. Luckily you do not need to use the actual memory location to access the data, but you can use the variable which is a symbolic name that references the memory location.

Primitive types are the most basic data types available within a programming language. These types serve as the building blocks of data manipulation. Such types serve only one purpose - containing pure, simple values of a certain type. Because these data types are defined into the type system by default, they come with a number of operations predefined (+, -, *, /, %, ...).

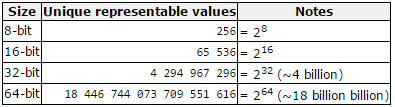

C++ supports several primitive datatypes as shown in the following table.

Primitive data types are basic types implemented directly by the language that represent the basic storage units supported natively by most systems. They can mainly be classified into:

- Character types: These can represent a single character, such as

'A'or'$'. The most basic type ischar, representing a single character. Other types are also provided for wider characters. - Numerical integer types: They can store a whole number value, such as

7or1024. They exist in a variety of sizes, and can either besignedorunsigned, depending on whether they support negative values or not. - Floating-point types: These types represent real values, such as

3.14or0.01, with different levels of precision, depending on which of the three floating-point types is used. - Boolean type: The boolean type, known in C++ as

bool, can only represent one of two states,trueorfalse.

While the bool type does represent a true or false value, in the background it is actually an integer value. false is represented with the value of 0 and true is represented with anything different from 0.

bool a = true;

bool b = false;

bool c = 0;

bool d = -15;

bool e = 23;

std::cout << "Value of a: " << a << std::endl;

std::cout << "Value of b: " << b << std::endl;

std::cout << "Value of c: " << c << std::endl;

std::cout << "Value of d: " << d << std::endl;

std::cout << "Value of e: " << e << std::endl;

Results in

Value of a: 1

Value of b: 0

Value of c: 0

Value of d: 1

Value of e: 1

WARNING - Datatype sizes

Note that the C++ standard does not specify a concrete size for each type. This means that the size of the data types actually dependent on the system you are compiling for. In certain situations you will need to keep this in mind.

Within each of the groups above, the difference between types is only their size (i.e., how much space they occupy in memory): the first type in each group is the smallest, and the last is the largest, with each type being at least as large as the one preceding it in the same group. Other than that, the types in a group have the same properties.

INFO - The fundamental storage unit in C++

From the draft version of the C++ 17 Standard $4.4/1 The fundamental storage unit in the C++ memory model is the byte. A byte is at least large enough to contain any member of the basic execution character set (5.3) and the eight-bit code units of the Unicode UTF-8 encoding form and is composed of a contiguous sequence of bits, the number of which is implementation defined.

Type sizes above are expressed in bits; the more bits a type has, the more distinct values it can represent. On the other hand, the larger the size, the more memory a datatype consumes.

Declaring variables

C++ is a strongly-typed language, and requires every variable to be declared with its type before its first use. This informs the compiler the size to reserve in memory for the variable and how to interpret its value. The syntax to define a new variable in C++ is straightforward: simply write the type followed by the variable name (also known as its identifier).

WARNING - Declaration versus definition

Note that defining a variable is not the same as declaring it. Declaring a variable is stating that it exists somewhere, while defining a variable is actually creating it. Declaring a variable is done using the

externkeyword. While less important for variables, the distinction will be more clear in the context of functions, methods and classes.

int radius; // Definition

double area; // Definition

char firstLetter = 'a'; // Definition + initialization

bool isSucces, isFinished; // Multiple definitions are possible as comma separated list

int sum = 0;

int average = 0.0;

As shown in the example above, you can also initialize the variable while defining it. When a value like 'a' or 0.0 is used inside code, it is called a literal value.

The name of a variable can be composed of letters, digits, and the underscore character. It must begin with either a letter or an underscore, not with a digit. Upper and lowercase letters are distinct because C++ is case-sensitive.

The Assignment Operator

The most used operator is the assignment operator =. It assigns a value to a variable. For example:

int x = 5;

int y = x; // Assign value of x to y

The last statement assigns the value of the variable x to the variable y. Consider also that we are only assigning the value of x to y at the moment of the assignment operation. Therefore, if x changes at a later moment, it will not affect the value held by y.

Variable initialization

While a variable does not need to be initialized, it should not be used before a meaningful value is assigned to it. Uninitialized variables in C++ actually cause garbage data and may cause unpredictable results if their value is used before they are assigned a decent value.

Try the following code example

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main() {

int a, b, c

cout << "a = " << a << endl;

cout << "b = " << b << endl;

cout << "c = " << c << endl;

return 0;

}

The output is undefined. Example:

a = 32765

b = 0

c = 0

Both C and C++ define the values as undefined. Undefined means it may be anything, including being initialized to 0, taking previous value of the memory, being initialized to 0xDEADBEEF or consecutive bytes of string "blarg! blarg! blarg!", or anything else. In modern operating systems memory is usually zeroed at start and hence short-lived programs will typically have 0s everywhere. Basically you're getting a random value, which happens to sometimes be 0. But it's not guaranteed to be 0.

So important lesson: Make sure to assign a meaningful value to variables before using them as they may lead to hard-to-track bugs inside your application.

Constants

In C++ there are two ways to define constant values:

- Using the preprocessor

#definedirective - Using the

constkeyword

Constants can be defined using a preprocessor directive using the following template.

#define IDENTIFIER <value>

Notice that no assignment operator or statement terminator is required.

An example:

#define MAX_NUMBER_OF_STUDENTS 25

When the application is compiled the preprocessor actually replaces all the occurrences of these directives with their actual values. Think of it as an automatic search and replace in your source code.

You can also use const prefix to declare constants with a specific type as follows:

const <datatype> VARIABLE_NAME = <value>;

For example:

const int NUMBER_OF_TEACHERS = 85;

A const variable declaration declares an actual variable in the language, which you can use like a real variable: take its address, pass it around, use it, cast it, convert it, etc.

Perhaps one might think that avoiding the declaration of a variable saves time and space, but with any sensible compiler optimization levels there will be no difference, as constant values are already substituted and folded at compile time. But you gain the huge advantage of type checking and making your code known to the debugger, so there's really no reason not to use const variables.

Typically constants are defined using an all CAPITALS name and underscores between the different words. This is a good programming practice.

Mathematical Operators

The most basic operators are the mathematical operators. They are easy to understand because they have the same functionality as in math. The following operators are available to do basic math operations:

+Additive operator (also used for String concatenation)-Subtraction operator*Multiplication operator/Division operator%Remainder operator

These operators are part of the binary operators because they take two operands, namely a left and a right operator. For example in the summation below L is the left operand and R is the right operand. The result of the operation is stored in the variable sum.

int R = 14;

int L = 12;

int result = L + R; // Result is now 26

The +, - and * operators function the same as in math. Their use can be seen in the code below.

int a = 2 + 3; // a = 5

int b = a + 5; // b = 10

int c = 6 * b; // c = 60

int d = c - 120; // d = -60

The division and remainder operators deserve some special attention. The division operator has a different result based on the types of its left and right operand. If both are of an integral type (short, int, byte) then a whole division will be performed. Meaning that 3 / 2 will result in 1. If either operand is a floating point operand (float or double) than the division operator will perform a real division: 3.0 / 2 will result in 1.5.

If your operands are of integral type and you wish to perform a real division, you can always multiply one of the operands with 1.0 to explicitly convert it to a floating point number without having to change its actual data type. Let us take a look at some examples.

int x = 5;

int y = 2;

int z = x / y; // z = 2 (whole division)

double w = x / y; // w = 2.0 (still whole division)

double q = 1.0 * x / y; // w = 2.5 (real division)

double a = 3.0;

double b = 2; // 2 will actually be converted to 2.0

double k = a / b; // k = 1.5 (real division)

Notice that even double w = x / y; results in 2.0. The reason behind this is that x / y equals to 2 as it is a whole division since both operand are of integral type. The result is then implicitly converted to a double, and stored in w.

While the precedence (order) in which mathematical operations are performed is defined in C++, most programmers do not know all of them by heart. It is much more clear and simpler to use round brackets () to enforce the precedence of the calculations. Take a look at the following piece of code:

int a = 5;

int b = 6;

int c = 10;

int d = 2;

int result = a * b + c - d * a / 5 - 3; // result = 35

std::cout << "The result is " << result << std::endl;

The result of the code above is 35. Would you have known? By using round brackets this becomes much clearer and the chance of making a mistake is a lot smaller.

int a = 5;

int b = 6;

int c = 10;

int d = 2;

int result = (a * b) + c - (d * a / 5) - 3; // result = 35

std::cout << "The result is " << result << std::endl;

Operators that have the same precedence are bound to their arguments in the direction of their associativity. For example, the expression a = b = c is parsed as a = (b = c) because of right-to-left associativity of assignment. The expression a + b - c is parsed (a + b) - c because of left-to-right associativity of addition and subtraction.

Compound Operators

Programmers are very lazy creatures that are always looking for ways to make their life's easier. That is why the compound operators were invented. They are a way to write shorter mathematical operations on the same variable as the result should be store in.

int x = 5;

x += 4; // Same as writing x = x + 4;

x -= 4; // Same as writing x = x - 4;

x *= 4; // Same as writing x = x * 4;

x /= 4; // Same as writing x = x / 4;

x %= 4; // Same as writing x = x % 4;

Increment and Decrement Operators

Incrementing (+1) and decrementing (-1) a variable is done very often in a programming language. It is one of the most used operations on integral values. It is most common used in loop-constructs as we will see in this chapter later on.

Because of this a shorter way has been introduced using an increment ++ or decrement -- operator as shown below.

int i = 5;

i++; // Same as writing i = i + 1;

i--; // Same as writing i = i - 1;

There is however a caveat to keep in mind. Both operators come in a suffix (e.g. i++) and a prefix (e.g. ++i) version. The end result of both versions is exactly the same, but there is a difference if you assign their value to another variable while using the increment or decrement operator.

Let us take a look at two examples. First we take a look at the prefix version. In this case the value of i will be incremented to 6 before its value assigned to the variable b. Meaning at the end of this code both i and b will have a value of 6.

int i = 5;

int b = ++i;

Next we take a look at the suffix version. In this case the value of i will first be assigned to b before it is incremented. This results in a b having a value of 5 and i having a value of 6 at the end of the example.

int i = 5;

int b = i++;

While this may not seem all that important at the moment we will require to know this once we start to work with arrays.

Comparison Operators

Comparison (aka relational) operators are used for comparison of two values.

The table below shows the available comparison operators that can be used in C++ to build a condition.

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

| == | equal to |

| != | not equal to |

| > | greater than |

| >= | greater than or equal to |

| < | less than |

| <= | less than or equal to |

Since a conditional statement actually produces a single true or false result, this result can actually be assigned to a variable of type bool.

Let's take a look at some examples of comparison operators:

int a = 4;

int b = 8;

bool result;

result = (a < b); // true

result = (a > b); // false

result = (a <= 4); // a smaller or equal to 4 - true

result = (b >= 9); // b bigger or equal to 9 - false

result = (a == b); // a equal to b - false

result = (a != b); // a is not equal to b - true

Note how we need to use two equality signs == to test if two values are equal, while we use a single sign = for assignment.

While the comparison operators will not often be used in a situation as shown in the code above, they will often be used when making decisions in your program.

Conditional Operators

When creating more complex conditional statements you will need to use the conditional operators to create combinations of conditions.

The table below gives an overview of the available conditional operators in C++.

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

| && | AND |

| || | OR |

| ! | NOT |

These work as you know them from the Boolean algebra. The || (OR) operator will return true if either of the operands evaluate to true. The && (AND) operator will return true if both operands evaluate to true. A logical expression can be negated by placing the ! (NOT) operator in front of it.

The code example below checks if a person is a child, an adult or an adolescent based on his/her age.

int age = 16;

bool isAChild = (age >= 0 && age <= 14); // false

bool isAnAdult = (age >= 18 && age <= 75); // false

bool isAnAdolescent = (age > 14 && age < 18); // true

Lazy Evaluation

The conditional operators exhibit "short-circuiting" behavior, which means that the second operand is evaluated only if needed. This is also called lazy evaluation. So for example in an OR statement, if the first operand evaluates to true the outcome must also be true. For this reason the second operand is not checked anymore.

This can lead to confusing C++ constructions which should be avoided when possible. However as a future professional C++ programmer you may encounter them and need to understand their behavior.

An example where the second operand of the condition is not checked:

int counter = 0;

bool result = (false && counter++);

std::cout << "Counter: " << counter << std::endl;

std::cout << "Result: " << result << std::endl;

with an output of

Counter: 0

Result: 0

And an example where the second operand of the condition is evaluated:

int counter = 0;

bool result = (true && counter++);

std::cout << "Counter: " << counter << std::endl;

std::cout << "Result: " << result << std::endl;

with an output of

Counter: 1

Result: 0

Do note that in the last example the postfix operator is used and not the prefix operator. Meaning that the value of counter is evaluated before it is incremented. As its initial value was 0 it is evaluated to false, meaning that result is assigned false.

The if statement

The statements inside your source files are generally executed from top to bottom (in the order that they appear). Control flow statements, however, break up the flow of execution by employing decision making, enabling your program to conditionally execute particular blocks of code. This section describes the if and if-else statements that allow code to be executed based on a given condition.

The if statement is the most basic of all the control flow statements. It allows an application to execute a certain section of code only if a particular condition evaluates to true.

Examine the following example where the user is requested to enter a temperature. Next the given value is evaluated and if it is above (or equal to) a certain threshold value (85 in this case) a warning message is outputted to the terminal.

int temperature = 0;

std::cout << "Please enter temperature: ";

std::cin >> temperature;

if (temperature >= 85) {

std::cout << "Warning, temperature is too high!" << std::endl;

}

If this test evaluates to false (meaning that the temperature is below 85), control jumps to the end of the if statement.

The if-else Statement

The if-else statement provides a secondary path of execution when an "if" clause evaluates to false. Taking the previous example you could output a "all is good" message when the temperature is below the threshold value.

int temperature = 0;

std::cout << "Please enter temperature: ";

std::cin >> temperature;

if (temperature >= 85) {

std::cout << "Warning, temperature is too high!" << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "All is good" << std::endl;

}

The if-else statement can be extended with even more if-else statements. Each if-else will need a new condition that needs to be checked. The first one that evaluates to true is executed, after which control jumps to the end of the if-else statements.

Let us extend the temperature example with a number of ranges.

int temperature = 0;

std::cout << "Please enter temperature: ";

std::cin >> temperature;

if (temperature < 85) {

std::cout << "All is good" << std::endl;

} else if (temperature >= 85 && temperature < 100) {

std::cout << "Warning, temperature is too high!" << std::endl;

} else if (temperature >= 100 && temperature <= 200) {

std::cout << "Time to run!" << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "We are doomed!!!!" << std::endl;

}

You may have noticed that the value of temperature can satisfy more than one expression in the combined statements. However the conditions are checked sequentially and once a condition is satisfied, the appropriate statements are executed and the remaining conditions are not evaluated anymore.

The Switch Statement

Let us take a look at some code that will allow the user to enter the number of the day of the week. The program will than determine the name of the day and output it to the user.

int dayOfTheWeek = 0;

std::cout << "What day of the week is it today [1-7]? ";

std::cin >> dayOfTheWeek;

if (dayOfTheWeek == 1) {

std::cout << "Than it's Monday today" << std::endl;

} else if (dayOfTheWeek == 2) {

std::cout << "Than it's Tuesday today" << std::endl;

} else if (dayOfTheWeek == 3) {

std::cout << "Than it's Wednesday today" << std::endl;

} else if (dayOfTheWeek == 4) {

std::cout << "Than it's Thursday today" << std::endl;

} else if (dayOfTheWeek == 5) {

std::cout << "Than it's Friday today" << std::endl;

} else if (dayOfTheWeek == 6) {

std::cout << "Than it's Saturday today" << std::endl;

} else if (dayOfTheWeek == 7) {

std::cout << "Than it's Sunday today" << std::endl;

} else {

std::cout << "That is not a valid number" << std::endl;

}

}

When checking a single variable for equality using multiple if-else statements, it can be replaced with another structure called a switch structure. The template of the switch structure is shown below. Each case needs a literal integral value to compare the variable against. If it matches (equals) than the code between the colon : and the break; statement is executed. The break is required for the switch to be stopped when a match is found. If no break is placed, the execution falls through to the next case.

switch (<variable>) {

case <integral_literal_1>:

// Code to be executed

break;

case <integral_literal_2>:

// Code to be executed

break;

case <integral_literal_3>:

// Code to be executed

break;

// ...

default:

// Code to be executed in case no match found

}

Replacing the if-else structure of the day-of-the-week example with a switch statement results in the following code.

int dayOfTheWeek = 0;

std::cout << "What day of the week is it today [1-7]? ";

std::cin >> dayOfTheWeek;

switch(dayOfTheWeek) {

case 1:

std::cout << "Than it's Monday today" << std::endl;

break;

case 2:

std::cout << "Than it's Tuesday today" << std::endl;

break;

case 3:

std::cout << "Than it's Wednesday today" << std::endl;

break;

case 4:

std::cout << "Than it's Thursday today" << std::endl;

break;

case 5:

std::cout << "Than it's Friday today" << std::endl;

break;

case 6:

std::cout << "Than it's Saturday today" << std::endl;

break;

case 7:

std::cout << "Than it's Sunday today" << std::endl;

break;

default:

std::cout << "That is not a valid number" << std::endl;

}

No general rule exists for when to use which construct. Some programmers don't like the switch statement. In most cases it is a case of preference.

Some important points about the switch statement:

The expression provided in the switch should result in a constant value otherwise it would not be valid.

- Valid expressions for switch:

// Constant expressions allowed switch(1+2+23) switch(1*2+3%4)- Invalid switch expressions for switch:

// Variable expression not allowed switch(ab+cd) switch(a+b+c)Duplicate case values are not allowed.

- The default statement is optional. Even if the switch case statement did not have a default statement, it would run without any problem.

- The break statement is optional. If omitted, execution will continue on into the next case. The flow of control will fall through to subsequent cases until a break is reached.

- Nesting of switch statements are allowed, which means you can have switch statements inside another switch. However nested switch statements should be avoided as it makes code more complex and less readable.

The for loop

Basically a for loop is most often used when the number of iterations is pre-determined. A typical example would be a list of items where an actions needs to be applied to each item in the list.

The syntax of a for loop in C++ is:

for ( <initialization>; <condition>; <increment> ) {

// statements

}

- The initialization step is executed first, and only once. This step allows you to declare and initialize any loop control variables. You are not required to put a statement here, as long as a semicolon appears.

- Next, the condition is evaluated. If it is

true, the body of the loop is executed. If it isfalse, the body of the loop does not execute and flow of control jumps to the next statement just after the for loop. - After the body of the for loop has executed, the flow of control jumps back up to the increment statement. This statement allows you to update any loop control variables. This statement can be left blank, as long as a semicolon appears after the condition.

- The condition is now evaluated again. If it is true, the loop executes and the process repeats itself (body of loop, then increment step, and then again condition). After the condition becomes false, the for loop terminates.

Each of these components are optional. However the semicolon used to distinguish between each part is mandatory.

An example of a simple for-loop that iterates between 0 and 9 and outputs each value of i.

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

cout << "i = " << i << endl;

}

Note that i actually has block scope here and will not be available outside of the for-loop. If you want to keep the last iteration value after the for-loop you need to define the iterator before the for-loop.

int i = 0;

for (; i < 10; i++) {

cout << "i = " << i << endl;

}

cout << "After the for-loop i = " << i << endl;

An endless loop would look like this.

for (;;;) {

// Do something forever

}

Functions

A function groups together a block of statements that inherently belong together. A functions performs a single well defined task. Every C++ program has at least one function, namely main(). By grouping together statements as a function we also allow the reuse of functionality inside our applications, which contributes to the DRYness of our code.

The C++ standard library provides numerous built-in functions that your program can call. Take a look at the reference of the standard C++ library at http://www.cplusplus.com/reference/.

Functions are given a symbolic name, allowing for easy calling of the functions and also making it more clear what the function does exactly (of course if the creator of the function gives it a clear and understandable name).

Calling Existing Functions

To call a function, you need to pass the required parameters along with the function name. If the function returns a value, then you can also store the returned value for later use. When a program calls a function, program control is transferred to the called function. A called function performs a defined task and when it is finished it returns program control back to the code that called the function, ready to execute the statement following the function call.

For example the max() function in the standard algorithm library compares the two arguments and returns the greatest of the two:

#include <iostream>

#include <algorithm>

int main() {

double biggest = std::max(3.14, 15.12);

std::cout << "max(3.14, 15.12) => " << biggest << std::endl;

return 0;

}

The max() function takes two arguments and returns the result. While the above code example shows an example with two literal values, it is also perfectly possible to pass variables. It is also possible to directly use the return value (without using the biggest variable in this case).

#include <iostream>

#include <algorithm>

int main() {

double pi = 3.14;

double someNumber = 15.12;

std::cout << "max(" << pi << ", " << someNumber << ") => " << std::max(pi, someNumber) << std::endl;

return 0;

}

But how does one know how to call a certain function? Simple: by reading the online reference or documentation and by trying to understand the examples. Start by taking a look at the documentation of the max() function: http://www.cplusplus.com/reference/algorithm/max/.

Creating Custom Functions

To create custom functions two components are required:

- A function declaration (also called the prototype), which tells the compiler about a function's name, return type, and its parameters;

- A function definition, which provides the actual body (implementation) of the function.

Defining a Function

The general form of a C++ function definition looks like the template below

<return_type> function_name( <comma_separated_parameter_list> ) {

// Statements (body / implementation)

return <value>; // In case of a non-void function

}

A C++ function definition consists of a function header (same as the prototype) and a function body:

- The return type: A function may return a value. The return type is the data type of the value the function returns. Some functions perform the desired operations without returning a value. In this case, the return type is the keyword

void. - The function name: This is the actual name of the function.

- Comma separated parameter list: A parameter is like a special local variable to the function. When a function is invoked, you pass a value to the parameter. This value is referred to as an actual parameter or argument. The parameter list refers to the type, order, and number of the parameters of a function. Parameters are optional; that is, a function may contain no parameters.

- Function body: The function body contains a collection of statements that together define what the function does.

The function name and the parameter list together constitute the function signature. Note that the return type is not part of the function signature. As the standard says in a footnote, "Function signatures do not include return type, because that does not participate in overload resolution".

INFO - Overload resolution

A function signature is the parts of the function declaration that the compiler uses to perform overload resolution. Since multiple functions might have the same name (ie., they're overloaded), the compiler needs a way to determine which of several possible functions with a particular name a function call should resolve to. The signature is what the compiler considers in that overload resolution.

If a function is to use arguments, it must declare variables that accept the values of the arguments. These variables are called the formal parameters of the function. The formal parameters behave like other local variables inside the function and are created upon entry into the function and destroyed upon exit.

Consider the function sum() shown below that determines the sum of two integral values.

int sum(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

Some things to note:

- The name of the function is

sum - The return value of the function is

intso it needs to have a return statement that returns an integer value - It takes two parameters, namely

aof typeintandbalso of typeint. Each parameter needs an explicit type specification.

Declaring a Function

A function declaration tells the compiler about a functions name and how to call the function. The actual body of the function can be defined separately.

A function declaration has the following parts:

<return_type> function_name( <comma_separated_parameter_list> );

In other words the function declaration is exactly the same as the function header but without the attached body found with the actual definition.

For the previous defined function sum(), the function declaration would be:

int sum(int a, int b);

Parameter names are not important in function declaration only their type is required, so following is also a valid declaration:

int sum(int, int);

A separate function declaration is required when you

- define a function below the point were you call the function (for example using a custom function in

main()that is defined below main) - define a function in one source file and you call that function in another file. In such case, you should declare the function at the top of the file calling the function.

Putting it all together

Below is an example of the sum() function being called from the main() function. Note that no declaration (prototype) is required as the sum() function is defined before main.

#include <iostream>

int sum(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

int main() {

std::cout << "sum of 12 and 15 = " << sum(12, 15) << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Now if one were to place the sum() function below main, the compiler would generate the error: error: 'sum' was not declared in this scope. This can be fixed by adding a declaration of the sum() function before main().

#include <iostream>

// Function declaration, comment out to see the compiler error

int sum(int a, int b);

int main() {

std::cout << "sum of 12 and 15 = " << sum(12, 15) << std::endl;

return 0;

}

int sum(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

Default parameter values

When you define a function, you can specify a default value for each of the last parameters. This value will be used if the corresponding argument is left blank when the function is called.

This is done by using the assignment operator and assigning values for the arguments in the function definition. If a value for that parameter is not passed when the function is called, the default value is used, but if a value is specified, this default value is ignored and the passed value is used instead.

Let us consider a function print_terminal() that prints out the terminal sign of a console (for example > in powershell).

void print_terminal(char sign = '>') {

std::cout << sign;

}

If no argument is passed, the default > is printed. In the other case the passed symbol is outputted.

#include <iostream>

void print_terminal(char sign = '>') {

std::cout << sign;

}

int main() {

// Using the default symbol

print_terminal();

std::cout << std::endl;

// Passing another symbol

print_terminal('$');

std::cout << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Default parameter values can be placed in the declaration and in the definition of a function but not in both. The most logical place is the declaration as this is most likely the only thing the user sees (the definition may be hidden as we will see later).

Functions versus methods

A function is a piece of code that is called by name. It can be passed data to operate on (i.e., the parameters) and can optionally return data (the return value). All data that is passed to a function is passed explicitly.

A method is a piece of code that is called by name that is associated with an object. In most respects it is identical to a function except for two key differences.

- It is implicitly passed a reference to the object for which it was called.

- It is able to operate on data that is contained within the class (remembering that an object is an instance of a class - the class is the definition, the object is an instance of that class).

Pass by value, by pointer or by reference

While calling a function, there are three ways that arguments can be passed to a function

- Pass by value: This copies the actual value of an argument into the formal parameter of the function. In this case, changes made to the parameter inside the function have no effect on the argument

- Pass by pointer: This copies the address of an argument into the formal parameter. Inside the function, the address is used to access the actual argument used in the call. This means that changes made to the parameter affect the argument.

- Pass by reference: This copies the reference of an argument into the formal parameter. Inside the function, the reference is used to access the actual argument used in the call. This means that changes made to the parameter affect the argument.

By default, C++ uses pass by value to pass arguments. In general, this means that code within a function cannot alter the arguments used to call the function.

Take for example the code below where a swap() function tries to swap the values of two variables.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void swap(int x, int y) {

int temp = x;

x = y;

y = temp;

}

int main() {

int a = 10;

int b = 136;

cout << "Before call to swap:" << endl;

cout << "a: " << a << endl;

cout << "b: " << b << endl;

swap(a, b);

cout << "\nAfter call to swap:" << endl;

cout << "a: " << a << endl;

cout << "b: " << b << endl;

return 0;

}

As C++ passes arguments by value, a copy of a and b is created and placed inside the local parameter variables x and y. Because of this changes to x and y are local to the scope of the function itself. Luckily enough because otherwise every function would be able to alter the original variables which would lead to a lot of bugs and hard to solve problems.

The output being:

Before call to swap:

a: 10

b: 136

After call to swap:

a: 10

b: 136

But what if we wanted this to work. Well then you need to pass the data using pointers or references. More on this later.

Overview of Keywords in C++

This is a list of reserved keywords in C++. Since they are used by the language itself, these keywords are not available for re-definition or overloading. This also implies that they cannot be used as names for variables.

| Keyword | Short description |

|---|---|

| alignas (since C++11) | - |

| alignof (since C++11) | - |

| and | - |

| and_eq | - |

| asm | - |

| auto(1) | - |

| bitand | - |

| bitor | - |

| bool | - |

| break | - |

| case | - |

| catch | - |

| char | - |

| char16_t (since C++11) | - |

| char32_t (since C++11) | - |

| class(1) | - |

| compl | - |

| concept (since C++20) | - |

| const | - |

| constexpr (since C++11) | - |

| const_cast | - |

| continue | - |

| decltype (since C++11) | - |

| default(1) | - |

| delete(1) | - |

| do | - |

| double | - |

| dynamic_cast | - |

| else | - |

| enum | - |

| explicit | - |

| export(1) | - |

| extern(1) | - |

| false | - |

| float | - |

| for | - |

| friend | - |

| goto | - |

| if | - |

| inline(1) | - |

| int | - |

| long | - |

| mutable(1) | - |

| namespace | - |

| new | - |

| noexcept (since C++11) | - |

| not | - |

| not_eq | - |

| nullptr (since C++11) | - |

| operator | - |

| or | - |

| or_eq | - |

| private | - |

| protected | - |

| public | - |

| register(2) | - |

| reinterpret_cast | - |

| requires (since C++20) | - |

| return | - |

| short | - |

| signed | - |

| sizeof(1) | - |

| static | - |

| static_assert (since C++11) | - |

| static_cast | - |

| struct(1) | - |

| switch | - |

| template | - |

| this | - |

| thread_local (since C++11) | - |

| throw | - |

| true | - |

| try | - |

| typedef | - |

| typeid | - |

| typename | - |

| union | - |

| unsigned | - |

| using(1) | - |

| virtual | - |

| void | - |

| volatile | - |

| wchar_t | - |

| while | - |

| xor | - |

| xor_eq | - |